By Adnan Habibja

Sweden is famous for its ambitious investments in wage subsidies. The programs have positive effects, but they are concentrated to low-qualified jobs in e.g. hotels and restaurants, retail, agriculture and the cleaning industry. Workers employed with wage subsidies have far lower wages than average workers, even adjusted for sectorial and occupational differences. For these reasons, this article questions whether the wage subsidies can be better described as a pathway to labour market segmentation, rather than integration. No published studies have discovered the reasons for the concentration. One is probably that many of the program participants have weak educational backgrounds, but there could also be regulation-based explanations. My analysis shows that the low government-set wage ceiling of 20,000 SEK/month may play an important role for the low wages of subsidy workers. A causal relationship exists between the wage ceiling and actual wages, since an increase of the wage ceiling in some programs in 2017 lead to decisions with higher wages, while a reduced wage ceiling resulted in lower wages. In other words, the low wage ceiling may, at least to some extent, explain the concentration of subsidy employments to low-paid jobs, which is new information for Swedish policy-makers. Thus, an increase of the wage ceiling could be an effective policy tool, not only to increase the wages of low-paid subsidy workers, but also to achieve a more even distribution of subsidised employment across the labour market.

For many decades, Sweden has been famous for its ambitious investments in active labour market policies. In previous articles, I have showed that Swedish governments have invested considerably more resources than comparable OECD-countries in different types of wage subsidies, especially during the last decades (e.g. Habibija 2020). Nearly 100,000 Swedish workers are hired with some kind of wage subsidy. The arguments are compelling. The purpose is to stimulate employers to hire persons who have difficulties in getting a job, and to facilitate the transition to ordinary employment. The Swedish subsidy programs have distinguishing characteristics but they have in common that the hiring company receives a substantial subsidy from the Public Employment Service (PES) for hiring either long-term unemployed individuals, newly arrived migrants, or unemployed with disabilities. The idea is that the financial compensation should compensate employers for expected or actual reduced productivity among groups with weak labour market opportunities, and thereby, generate a broader inclusion on the labour market. Earlier research has found positive employment effects, but also positive effects on the employment development of the hiring companies and their financial results (e.g. Forslund 2018, Nordström Skans et. al. 2018).

- Concentration among low-paid jobs

Some studies, however, observe that subsidised employments are heavily concentrated in some specific segments of the labour market, more specifically to low-paid and low-qualified service jobs (e.g. Frödin and Kjellberg 2020). This is also what I find when analysing data from the Swedish Public Employment Service.

A relatively small share – approximately 2-3 percent – of the Swedish labour force has been employed with some kind of wage subsidy during the last years, but the variation between sectors and occupations is remarkable. As figure 1 illustrates, wage subsidies are uncommon in traditionally male-dominated industries, such as the manufacturing or construction industry, where about 2 percent of the workers have had a wage subsidy in recent years. Even though the demand for labour in health services and the education sector is strong, wage subsidies are very rare. Instead, subsidised employment is prevalent in retail and personal and cultural services. Nearly 10 percent of the workers in hotels and restaurants are employed with a wage subsidy.

Figure 1. Share of workers employed with a wage subsidy of total workers within the industry, 2016–2020

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | ||||||

| Manufacturing, energy and climate | 2,2% | 2,2% | 2,1% | 2,0% | 1,7% | |||||

| Construction and facility | 3,5% | 3,1% | 3,0% | 2,6% | 2,3% | |||||

| Retail | 4,2% | 3,9% | 3,7% | 3,5% | 3,3% | |||||

| Transport | 2,5% | 2,3% | 1,9% | 1,8% | 1,6% | |||||

| Hotel och restaurants | 9,1% | 8,7% | 8,5% | 8,7% | 8,1% | |||||

| Administration, business, finance, law, IT, and management | 2,8% | 2,9% | 2,9% | 2,6% | 2,2% | |||||

| Education | 1,8% | 1,9% | 2,0% | 1,8% | 1,7% | |||||

| Healthcare and related welfare services | 1,6% | 1,5% | 1,6% | 1,5% | 1,3% | |||||

| Personal and cultural services | 8,3% | 7,4% | 7,0% | 6,7% | 5,9% | |||||

Additional data show that the subsidies are very scarce in occupations with high educational requirements. In 2020, only 0.2 percent of the workers who had jobs that require an advanced university degree were employed with a subsidy. However, the wage subsidies are frequent in occupations with low educational requirements. About 10 percent of the workers in the agricultural sector had some kind of wage subsidy in 2016-2020. Almost 20 percent of the workers in Statistics Sweden’s occupation category 9 – jobs with very low educational requirements – e.g. street vendors and cleaners, were employed with a wage subsidy.

Data from PES decisions 2016-2020 show that workers with wage subsidies have far lower wages than average workers, even when sectoral and occupational differences are taken into account. The average gross salary among 77,000 workers with four types of subsidy programs was 20,228 SEK/month. The average gross salary among 153,000 workers with “new starts jobs” (a program targeted to unemployed with a better labour market position) was 22,467 SEK/month. These levels is far underneath the average salary on the Swedish labour market, which in 2020 was 36,100 SEK/month.

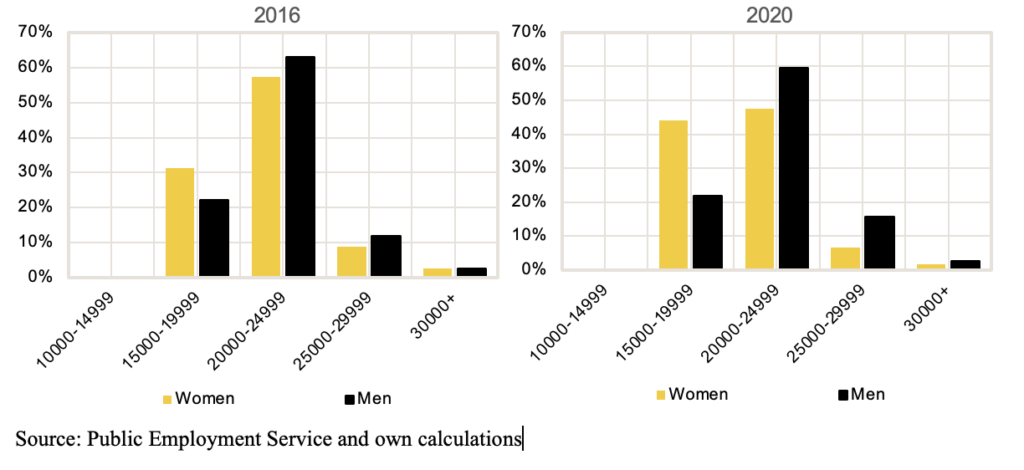

Figure 2 demonstrates a gender difference in the wages. The graph categorises the wages in wages subsidy decisions from 2016 and 2020 into different wage intervals. About 60 percent of the male workers with wage subsidies had a wage between 20,000 and 24,999 SEK/month, both years. The share with a wage between 25,000 and 29,999 SEK/month increased from 12 to 16 percent. More men than before were employed with higher wages – a logical development when annual pay rises are taken into account.

For female workers, however, the trend is the opposite. The share with a wage higher than 25,000 SEK/month has slightly decreased over the years. The share with a wage between 20,000 and 24,999 SEK/month decreased from 57 to 48 percent, while the share with a wage lower than 20,000 SEK increased significantly. Almost half of the female workers had a salary between 15,000 and 19,999 SEK/month in 2020, compared to 22 percent of the male workers. Very few, both women and men, have salaries higher than 30,000 SEK/month.

2. Effects from a wage subsidy reform

No published studies have discovered the explanations for the concentration of wage subsidies in low-paid jobs. One important reason is probably that many of the program participants have weak educational backgrounds and do not have sufficient skills to perform more high-skilled, and often well-paid, work, but there could also be some systematic and regulation-based explanations. The hypothesis of my study is that the low government-set wage ceiling of 20,000 SEK/month may play a role for the low wages of the individuals who are employed with wage subsidies. The wage ceiling is designed so that a company employing a person with a wage subsidy will not receive any compensation for the part of the wage that exceeds this amount. The subsidy programs may be more attractive for employers paying low wages, since a larger part of the wage cost is subsidised.

To test if a causal relationship exists between the wage ceiling and the actual wages in PES decisions, I have analysed the wage effects of changes in the wage ceiling which the Swedish government implemented in 2017. During the social democratic led government’s term of office 2014-2018, efforts were made to harmonise the different wage ceilings of different wage subsidy programs. The harmonisation took place 1st November 2017. Three programs that had a wage ceiling lower than 20,000 SEK/month were merged into the new program “introduction jobs”, and the wage ceiling was increased to 20,000 SEK/month. For “new start jobs”, which previously had a wage ceiling of 22,000 SEK/month, the wage ceiling was reduced to 20,000 SEK/month. These changes, which are summarised in the table below, are ideal for regression analyses.

- Figure 3. Summary of previous and new wage ceiling levels for some of the Swedish wage subsidy programs

| Previous wage ceiling | New wage ceiling 2017* | |

| Särskilt anställningsstöd / Special Recruitment Incentive | 17,300 SEK | – |

| Förstärkt särskilt anställningsstöd / Reinfoced Special Recruitment Incentive | 17,300 SEK | – |

| Instegsjobb / Entry Recruitment Incentive | 16,500 SEK | – |

| Introductionsjobb / Introductory job | – | 20,000 SEK |

| Nystartsjobb / New start job | 22.000 SEK | 20,000 SEK |

| Extratjänst / Extra services | 18,800 SEK | 20,000 SEK |

Source: Swedish Government, SFS 2017:885, SFS 2017:886

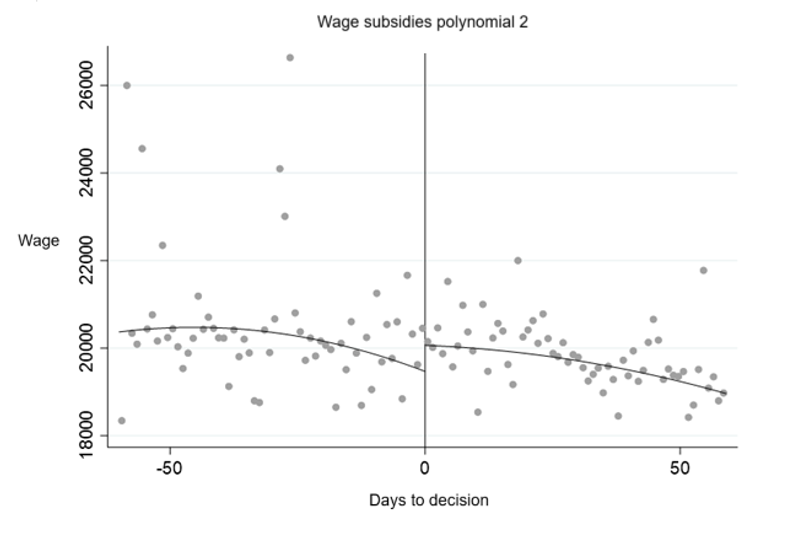

By using an RDD-approach (Regression-discontinuity-design) and two unique sets of decision data from PES; one for subsidy programs for which the wage ceiling increased, and the other one for new start jobs, where the wage ceiling decreased, I compare the actual wages in the decisions made precisely before and after the wage ceiling changes. The average wage difference is assumed to be a consequence of the reform. Figure 4 shows the effect of the increase in the wage ceiling to 20,000 SEK/month. The dots in the graph show the average wage of all workers who have received subsidy employments a specific day. The X-axis shows if the decision was made before or after the increase of the wage ceiling. The graph shows that the wages were lower before the increase of the wage ceiling. The wage ceiling increase resulted in an average wage increase of about 600 SEK/month. The effect is statistically significant on a 5 percent level, but the level is somewhat different depending on the method choices within RDD (several regressions are presented in Habibija 2022).

- Figure 4. RDD-analysis (wage subsidy program excluding new start jobs), band with 60 days

Source: Public Employment Service and own calculations

An equivalent analysis was made for new start jobs, for which the wage ceiling was reduced. The effect was not as strong for the other programs, but still statistically significant on a 5 percent level. The salaries in the decisions were on average a couple of hundreds SEK lower after the wage ceiling reduction.

3. Conclusions

The results indicate that an increased wage ceiling, ceteris paribus, leads to decisions with higher wages, while a reduced wage ceiling results in lower wages. Therefore, the conclusion is that a causal relationship exists between the wage ceiling and actual wages in the decisions made by PES. In other words, the low government-set wage ceiling may play an important role for the concentration of subsidy employments to low-paid jobs, which is new information for policy-makers and other stakeholders.

There are several arguments for a wage ceiling increase. The wage levels are important for the household economies, especially for workers with wages around today’s low level. The low wage ceiling put a downward pressure on wages for workers with wage subsidies, both by low initial salaries and poor wage growth. But the level of the wage ceiling is also important from a socioeconomic perspective, since a low wage ceiling can lead to a concentration of subsidised employment to low-paid jobs and a pressure on reservation wages. The wage ceiling implies that the subsidy is a fixed amount for full-time work, and the grade of subsidisation is lower when the wage is higher. Reasonably, this makes employers more reluctant to test an employee in a subsided employment when the wage is higher, which could be one explanation for the concentration to low-paid jobs. Thus, a low wage ceiling limits within which labour market segments employers receive compensation for expected or actual reduced productivity. A strong concentration to some labour market segments can distort competition among companies and lead to an overuse of wage subsidies (i.e. the condition when companies systematically recruit workers with subsidies only to reduce their staff costs, without intentions to offer long-term contracts).

The wage ceiling should, however, not be unreasonably high or unlimited, as was the case for new start jobs before 2015. The fact that there were salary payments over 100,000 SEK/month, as shown in the public inquiry SOU 2014:16, should be seen as a clear indication that there was an overuse and fraud involving new starts jobs due to the lack of a wage ceiling. In my opinion, the wage ceiling should be set around the average wage in the labour market, to open up a larger proportion of the labour market for wage subsidies, and to eliminate the mechanisms that risk leading to low initial salaries and weak wage growth for workers with wage subsidies. To continue counteracting these mechanisms in the future, it would be appropriate to ensure that the wage ceiling follows the wage growth by an annual indexation.

References

Forslund, A (2018), ”Subventionerade anställningar. Avvägningar och empirisk evidens”, IFAU-report 2018:14. The Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy. Uppsala.

Frödin, O och A, Kjellberg (2020), ”Anställningsbidrag: integration eller etnisk segmentering?”. Department of Sociology, Lund University, Lund.

Habibija, A (2020), ”Vad har hänt med den aktiva arbetsmarknadspolitiken?”, Ekonomisk Debatt, year 48, no. 6, page 8–20.

Habibija, A (2022), ”Etablering eller segmentering? En analys av systemet med subventionerade anställningar”, the Swedish Trade Union Confederation, Stockholm.

Nordstrom Skans et al (2018), ”Hur påverkar anställningsstöd och nystartsjobb de anställande företagen?”. IFAU-report 2018:13. The Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy. Uppsala.

Public Inquiry (2014), “Det ska vara lätt att göra rätt”, SOU 2014:16 Betänkande av ”Utredningen om åtgärder mot felaktiga utbetalningar inom den arbetsmarknadspolitiska verksamheten”, Ministry of Employment, Stockholm.

Statistics Sweden (2021). Wage data for 2020.

Statistics Sweden (2021). Labour Force Studies (AKU) for 2016-2020.

Swedish Government (2017) SFS 2017:885 “Förordning om ändring i förordningen (2006:1481) om stöd för nystartsjobb”. Ministry of Employment, Stockholm.

Swedish Government (2017). SFS 2017:886 “Förordning om ändring i förordningen (2015:503) om särskilt anställningsstöd”. Ministry of Employment, Stockholm.

Swedish Government (2018). SFS 2018:42 “Förordning (2018:42) om särskilt anställningsstöd”. Ministry of Employment, Stockholm.

Swedish Public Employment Service (2021. Decision data on wage subsidy programs excluding new start jobs. Delivered 2021-11-18.

Swedish Public Employment Service (2021). Decision data on new start jobs. Delivered 2021-11-18.

Swedish Public Employment Service (2024), Published data on individuals employed with differed types of wage subsidies.